This article is a dive into the realms of Event Sourcing, Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS), Change Data Capture (CDC), and the Outbox Pattern. Much needed clarity on the value of these solutions will be presented. Additionally, two differing designs will be explained in detail with the pros/cons of each.

So why do all these solutions even matter? They matter because many teams are building microservices and distributing data across multiple data stores. One system of microservices might involve relational databases, object stores, in-memory caches, and even searchable indexes of data. Data can quickly become lost, out of sync, or even corrupted therefore resulting in disastrous consequences for mission critical systems.

Solutions that help avoid these serious problems are of paramount importance for many organizations. Unfortunately, many vital solutions are somewhat difficult to understand; Event Sourcing, CQRS, CDC, and Outbox are no exception. Please look at these solutions as an opportunity to learn and understand how they could apply to your specific use cases.

As you will find out at the end of this article, I will propose that three of these four solutions have high value, while the other should be discouraged except for the rarest of circumstances. The advice given in this article should be evaluated against your specific needs, because, in some cases, none of these four solutions would be a good fit.

Reactive Systems

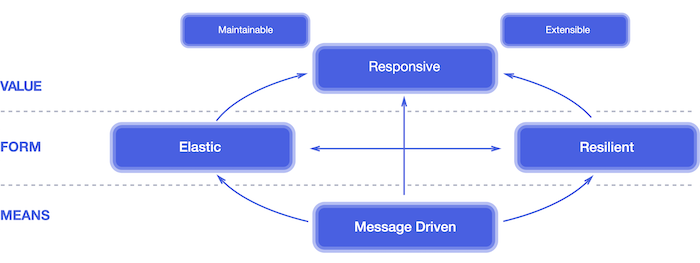

Taking a quick step back, Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture are solutions that can be used to build distributed systems (i.e. microservices) that are Reactive. Microservices should react to an ever-changing environment (i.e. the cloud) by being resilient and elastic. The magic behind these abilities is being message and event driven. To find out more, I advise you to read the Reactive Manifesto.

Figure 1. Attributes of a Reactive System, per the Reactive Manifesto

Shared Goals for Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture

The two core solutions presented in this article are Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture. Before I formally introduce these two solutions, it can be known that they serve similar goals, which are:

-

Designate one datastore as the global source of truth for a specific set of data

-

Provide a representation of past and current application state as a series of events, also called a journal or transaction log

-

Offer a journal that can replay events, as needed, for rebuilding or refreshing state

Event Sourcing uses its own journal as the source of truth, while Change Data Capture depends on the underlying database transaction log as the source of truth. This difference has major implications on the design and implementation of software which will be presented later in this article.

Domain Events vs. Change Events

Before we go deeper, it’s important to make a distinction about the types of events we are concerned about for Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture:

-

Domain events — An explicit event, part of your business domain, that is generated by your application. These events are usually represented in the past tense, such as OrderPlaced, or ItemShipped. These events are the primary concern for Event Sourcing.

-

Change events — Events that are generated from a database transaction log indicating what state transition has occurred. These events are of concern for Change Data Capture.

Domain events and change events are not related unless a change event happens to contain a domain event, which is a premise for the Outbox Pattern to be introduced later in the article.

Now that we have established some commonality on Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture, we can go deeper.

Event Sourcing

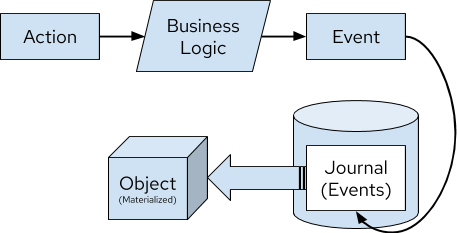

Event Sourcing is a solution that allows software to maintain its state as a journal of domain events. As such, taking the journal in its entirety represents the current state of the application. Having this journal also gives the ability to easily audit the history and also to time travel and reproduce errors generated by previous state.

Event Sourcing implementations usually have these characteristics:

-

Domain events generated from the application business logic will add new state for your application

-

State of the application is updated via an append-only event log (a journal) that is generally immutable

-

Journal is considered the source of truth for the lifetime of the application

-

Journal is replayable to rebuild the state of the application at any point in time

-

Journal groups domain events by an ID to capture the current state of an object (an Aggregate from DDD parlance)

Figure 2. Representation of Event Sourcing Materializing an Object

Additionally, Event Sourcing implementations often have these characteristics:

-

Snapshotting mechanism for the journal to speed up recreating the state of an application

-

Mechanism to remove events from the journal as required (usually for compliance reasons)

-

API for event dispatching that may be used for distributing state of the application

-

Lack of transactional guarantees that are normally present for a strongly consistent system

-

Backward compatibility mechanism to cope with changing event formats inside the journal

-

Mechanism to backup and restore the journal, the source of truth for the application

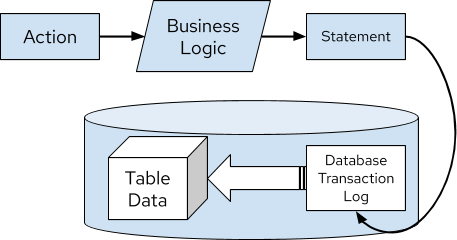

Event sourcing mimics how a database works, but at the application-level. Per Figure 2, the figure could be updated to represent a database as shown in Figure 3 with roughly the same design.

Figure 3. Representation of Database Transaction Materializing a Table

The comparison between Figure 2 and Figure 3 will become more relevant as we dive deeper into how Event Sourcing and Change Data Capture compare to each other.

Change Data Capture

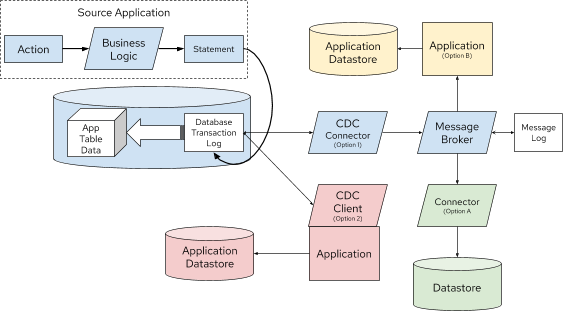

Change Data Capture (CDC) is a solution that captures change events from a database transaction log (or equivalent mechanism) and forwards those events to downstream consumers. CDC ultimately allows application state to be externalized and synchronized with external stores of data.

Change Data Capture implementations usually have these characteristics:

-

External process that reads the transaction log of a database with the goal to materialize change events from those transactions

-

Change events are forwarded to downstream consumers as messages

As you can see, CDC is a relatively simple concept with a very narrow scope. It’s simply externalizing the transaction log of the database as a stream of events to interested consumers.

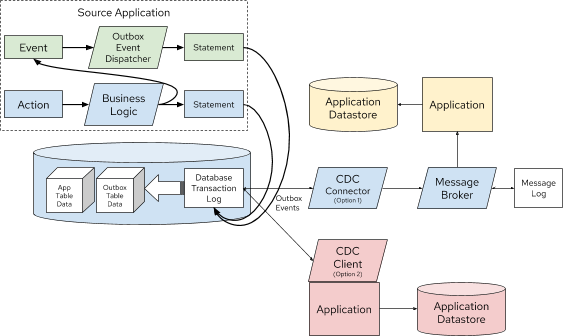

Figure 4. Change Data Capture Implementation Options

CDC also gives you flexibility on how events are consumed. Per Figure 4:

-

Option 1 is a standalone CDC process to capture and forward events from the transaction log to a message broker

-

Option 2 is an embedded CDC client that sends events directly to an application

-

Option A is another connector that persists CDC events directly to a datastore

-

Option B forwards events to consuming applications via a message broker

Finally, a CDC implementation often has these characteristics:

-

A durable message broker is used to forward events with at-least-once delivery guarantees to all consumers

-

The ability to replay events from the datastore transaction log and/or message broker for as long as the events are persisted

CDC is very flexible and adaptable for multiple use cases. Early adopters of CDC were choosing Option 1/A, but Option 1/B, and also Option 2 are becoming more popular as CDC gains momentum.

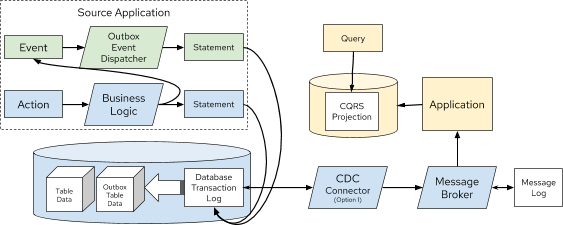

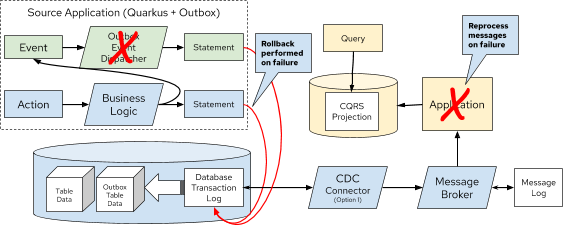

Using CDC to Implement the Outbox Pattern

The primary goal of the Outbox Pattern is to ensure that updates to the application state (stored in tables) and publishing of the respective domain event is done within a single transaction. This involves creating an Outbox table in the database to collect those domain events as part of a transaction. Having transactional guarantees around the domain events and their propagation via the Outbox is important for data consistency across a system.

After the transaction completes, the domain events are then picked up by a CDC connector and forwarded to interested consumers using a reliable message broker (see Figure 5). Those consumers may then use the domain events to materialize their own aggregates (see above per Event Sourcing).

Figure 5. Outbox Pattern implemented with CDC (2 Options)

The Outbox is also meant to be abstracted from the application as it’s only an ephemeral store of outgoing event data, and not meant to be read or queried. In fact, the domain events residing in the Outbox may be deleted immediately after insertion!

Event Sourcing Journal vs. Outbox

We can now take a closer look at the overlap in design of an Event Sourcing journal and CDC with Outbox. By comparing the attributes of the journal with the Outbox table, the similarities become clear. The Aggregate, again from DDD, is at the heart of how the data is stored and consumed for both Outbox and Event Sourcing.

Here are the common attributes that exist between an Event Sourcing journal and an Outbox:

-

Event ID — Unique identifier for the event itself and can be used for de-duplication for idempotent consumers

-

Aggregate ID — Unique identifier used to partition related events; these events compose an Aggregate’s state

-

Aggregate Type — The type of the Aggregate that can be used for routing of events only to interested consumers

-

Sequence/Timestamp — A way to sort events to provide ordering guarantees

-

Message Payload — Contains the event data to be exchanged in a format readable by downstream consumers

The Outbox table and the Event Sourcing journal have essentially the same data format. The major difference is that the Event Sourcing journal is meant to be a permanent and immutable store of domain events, while the Outbox is meant to be highly ephemeral and only be a landing zone for domain events to be captured inside change events and forwarded to downstream consumers.

Command Query Responsibility Segregation

The Command Query Responsibility Segregation pattern, or CQRS for short, is commonly associated with Event Sourcing. However, Event Sourcing is not required to use CQRS. For example, the CQRS pattern could instead be implemented with the Outbox Pattern.

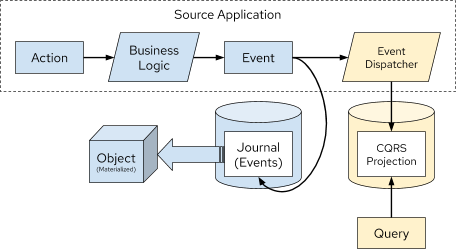

So what is CQRS anyways? It’s a pattern to create alternative representations of data, known as projections, for the primary purpose of being read-only, queryable views on some set of data. There may be multiple projections for the same set of data of interest to various clients.

The Command aspect to CQRS applies to an application processing actions (Commands) and ultimately generating domain events that can be used to create state for a projection. That is one reason why CQRS is so often associated with Event Sourcing.

Another reason why CQRS pairs well with Event Sourcing is because the journal is not queryable by the application. The only viable way to query data in an event sourced system is through the projections. Keep in mind, these projections are eventually consistent. This brings flexibility but also complexity and deviation from the norm of strongly consistent views that developers may be familiar with.

Figure 6. Representation of Event Sourcing with CQRS

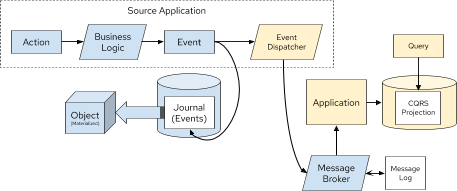

Figure 7. Representation of Event Sourcing with CQRS using a Message Broker

As you can see in Figure 6 and Figure 7, these are two very different interpretations of the CQRS pattern based on Event Sourcing, but the end result is the same, a queryable projection of data originating only from events.

As stated earlier, CQRS can also be paired with the Outbox Pattern, as shown in Figure 8. An advantage with this design is there is still strong consistency within the application database but eventual consistency with the CQRS projections.

Figure 8. Representation of the Outbox Pattern with CQRS

Processing Domain Events Internally

While this article is very focused on distributing data across a system, using domain events internally for an application can also be important. Processing domain events internally is necessary for a variety of reasons which includes executing business logic within the same microservice context as the event originated from. This is common practice for building event-driven applications.

With either Event Sourcing or CDC, processing domain events internally requires a dispatcher mechanism to pass the event in memory. Some examples of this would be the Vert.x EventBus, Akka Actor System, or Spring Application Events. In the case of the Outbox pattern, the event would be dispatched only after the initial Outbox transaction completes successfully.

Comparison of Attributes

This article has thrown a lot at you, so a table summarizing what has been presented so far may be beneficial:

| Attribute | Event Sourcing | CDC | CDC + Outbox | CQRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Purpose |

Capture state in a journal containing domain events. |

Export Change Events from transaction log. |

Export domain events from an Outbox via CDC. |

Use domain events to generate projections of data. |

Event Type |

Domain Event |

Change Event |

Domain Event embedded in Change Event |

Domain Event |

Source of Truth |

Journal |

Transaction Log |

Transaction Log |

Depends on implementation |

Boundary |

Application |

System |

System (CDC) Application (Outbox) |

Application or System |

Consistency Model |

N/A (only writing to the Journal) |

Strongly Consistent (tables), Eventually Consistent (Change Event capture) |

Strongly Consistent (Outbox), Eventually Consistent (Change Event capture) |

Eventually Consistent |

Replayability |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Depends on implementation |

Pros/Cons of Event Sourcing + CQRS

Now that we have a better handle on Event Sourcing and CQRS, let’s examine some of the pros and cons of Event Sourcing when paired with CQRS. These pros/cons take into consideration the current implementations that are available and also documented experiences from both myself and other professionals building distributed systems.

Pros for Event Sourcing with CQRS

-

Journal is easily accessible for auditing purposes

-

Generally performant for a high volume of write operations to the Journal

-

Possibility to shard the Journal for a very large amount of data (depending on datastore)

Cons for Event Sourcing with CQRS

-

Everything is eventually consistent data; a requirement of strongly consistent data doesn’t fit Event Sourcing and CQRS

-

Cannot read your own writes to the journal (from a query perspective)

-

Long term maintenance concerns around the journal and an event sourced architecture

-

Need to write a lot of code for compensating actions for error cases

-

No real transactional guarantees for resolving the dual writes flaw (to be covered next)

-

Need to consider backward compatibility or migration of legacy data as the formats of events change

-

Need to consider snapshotting the journal and the implications associated with it

-

Talent pool for developers with experience using Event Sourcing and CQRS is virtually nonexistent

-

Lack of use cases for Event Sourcing limits applicability

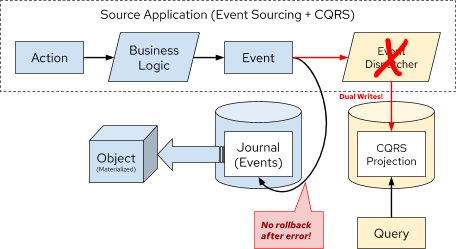

Dual Writes Risk for Event Sourcing and CQRS

One problem with Event Sourcing is that there is a possibility of failure to update the CQRS projections if there is an error with the application. This could result in missing data, and unfortunately, it may be difficult to recover that data without proper compensating actions built into the application itself. That is additional code and complexity that falls onto the developer, and is error prone. For example, one workaround is to track a read offset number that correlates to the event sourced journal, to give replayability upon error for reprocessing the domain events and refresh the CQRS projections.

The underlying reason for this possibility of errors is the lack of transactions for writing to both the Journal and the CQRS projections. This is what is known as “dual writes”, and it greatly increases the risk for errors. This dual writes flaw is represented in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Lack of Transactional Integrity with Event Sourcing and CQRS

Even adding a message broker, as shown in Figure 7 would not resolve the dual writes issue. With that design, you are still writing out the message to a message broker and an error could arise.

The dual writes flaw is just one example of some of the challenges in working with Event Sourcing with CQRS. Additionally, the long term maintenance and Day 2 impact of having the journal as the source of truth increases risk for your application over time. Event sourcing is also a paradigm that is unfamiliar to most engineers and is easy to make wrong assumptions or bad design choices that ultimately may lead to rearchitecting parts of your system.

Given the pros and cons about Event Sourcing paired with CQRS, it’s advisable to seek out alternatives before settling on this design. Your use case may fit Event Sourcing but CDC may also fit the bill.

Debezium for CDC and Outbox

Debezium is an open source CDC project supported by Red Hat that has gradually gained popularity over the past few years. Recently, Debezium added full support for the Outbox Pattern with an extension to the Quarkus Java microservice runtime.

Debezium, Quarkus, and the Outbox offer a comprehensive solution which avoids the Dual Writes flaw, and is generally a more practical solution for your average developer team as compared to Event Sourcing solutions.

Figure 10. Error Handling of the Outbox Pattern with CQRS

Pros for CDC + Outbox with Debezium

-

Source of truth stays within the application database tables and transaction log

-

Transactional guarantees and reliable messaging greatly reduce possibility for data loss or corruption

-

Flexible solution that fits into a prototypical microservice architecture

-

Simpler design is easier to maintain over the long term

-

Can read and query your own writes

-

Opportunity for strong consistency within the application database; eventual consistency across the remainder of the system

Cons for CDC + Outbox with Debezium

-

Additional latency may be present by reading the transaction log and also going through a message broker; tuning may be required for minimizing latency

-

Quarkus, while great, is the only current option for an off the shelf Outbox API; You could also roll your own implementation if needed

Conclusion

Building distributed systems, even with microservices, can be very challenging. That is what makes novel solutions like Event Sourcing appealing to consider. However, CDC and Outbox using Debezium is usually a better alternative to Event Sourcing, and is compatible with the CQRS pattern to boot. While Event Sourcing may still have value in some use cases, I encourage you to give Debezium and the Outbox a try first.

Further Reading

Docs and Repos

Blogs and Articles

About Debezium

Debezium is an open source distributed platform that turns your existing databases into event streams, so applications can see and respond almost instantly to each committed row-level change in the databases. Debezium is built on top of Kafka and provides Kafka Connect compatible connectors that monitor specific database management systems. Debezium records the history of data changes in Kafka logs, so your application can be stopped and restarted at any time and can easily consume all of the events it missed while it was not running, ensuring that all events are processed correctly and completely. Debezium is open source under the Apache License, Version 2.0.

Get involved

We hope you find Debezium interesting and useful, and want to give it a try. Follow us on Twitter @debezium, chat with us on Zulip, or join our mailing list to talk with the community. All of the code is open source on GitHub, so build the code locally and help us improve ours existing connectors and add even more connectors. If you find problems or have ideas how we can improve Debezium, please let us know or log an issue.