Updating external full text search indexes (e.g. Elasticsearch) after data changes is a very popular use case for change data capture (CDC).

As we’ve discussed in a blog post a while ago, the combination of Debezium’s CDC source connectors and Confluent’s sink connector for Elasticsearch makes it straight forward to capture data changes in MySQL, Postgres etc. and push them towards Elasticsearch in near real-time. This results in a 1:1 relationship between tables in the source database and a corresponding search index in Elasticsearch, which is perfectly fine for many use cases.

It gets more challenging though if you’d like to put entire aggregates into a single index. An example could be a customer and all their addresses; those would typically be stored in two separate tables in an RDBMS, linked by a foreign key, whereas you’d like to have just one index in Elasticsearch, containing documents of customers with their addresses embedded, allowing you to efficiently search for customers based on their address.

Following up to the KStreams-based solution to this we described recently, we’d like to present in this post an alternative for materializing such aggregate views driven by the application layer.

Overview

The idea is to materialize views in a separate table in the source database, right in the moment the original data is altered.

Aggregates are serialized as JSON structures (which naturally can represent any nested object structure) and stored in a specific table. This is done within the actual transaction altering the data, which means the aggregate view is always consistent with the primary data. In particular this approach isn’t prone to exposing intermediary aggregations as the KStreams-based solution discussed in the post linked above.

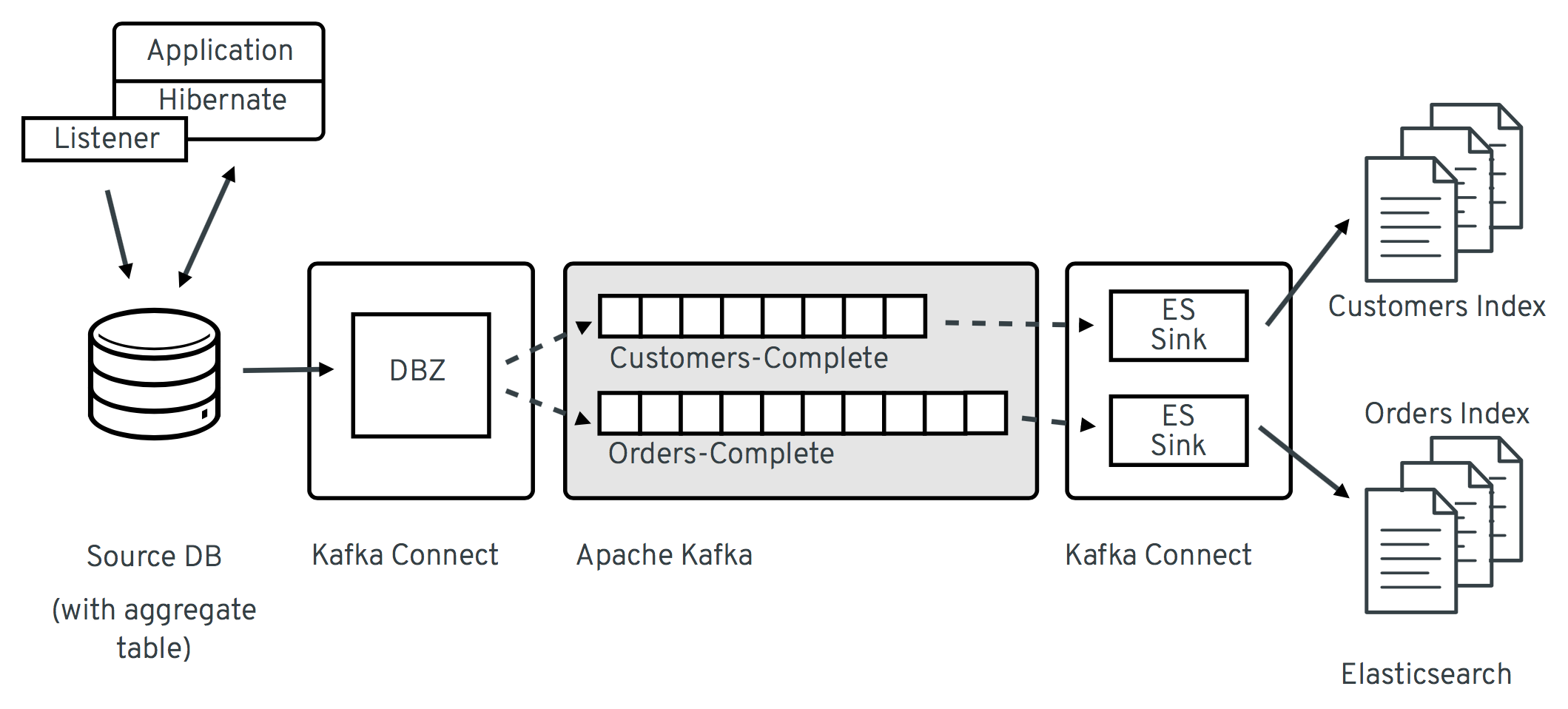

The following picture shows the overall architecture:

Here the aggregate views are materialized by means of a small extension to Hibernate ORM, which stores the JSON aggregates within the source database (note "aggregate views" can be considered conceptually the same as "materialized views" as known from different RDBMS, as in that they materialize the result of a "join" operation, but technically we’re not using the latter to store aggregate views, but a regular table). Changes to that aggregate table are then captured by Debezium and streamed to one topic per aggregate type. The Elasticsearch sink connector can subscribe to these topics and update corresponding full-text indexes.

You can find a proof-of-concept implementation (said Hibernate extension and related code) of this idea in our examples repository. Of course the general idea isn’t limited to Hibernate ORM or JPA, you could implement something similar with any other API you’re using to access your data.

Creating Aggregate Views via Hibernate ORM

For the following let’s assume we’re persisting a simple domain model

(comprising a Customer entity and a few related ones like Address, (customer) Category etc.) in a database.

Using Hibernate for that allows us to make the creation of aggregates fully transparent to the actual application code using a Hibernate event listener.

Thanks to its extensible architecture, we can plug such listener into Hibernate just by adding it to the classpath,

from where it will be picked up automatically when bootstrapping the entity manager / session factory.

Our example listener reacts to an annotation, @MaterializeAggregate,

which marks those entity types that should be the roots of materialized aggregates.

@Entity

@MaterializeAggregate(aggregateName="customers-complete")

public class Customer {

@Id

private long id;

private String firstName;

@OneToMany(mappedBy = "customer", fetch = FetchType.EAGER, cascade = CascadeType.ALL)

private Set<Address> addresses;

@ManyToOne

private Category category;

...

}Now if any entity annotated with @MaterializeAggregate is inserted, updated or deleted via Hibernate,

the listener will kick in and materialize a JSON view of the aggregate root (customer) and its associated entities (addresses, category).

Under the hood the Jackson API is used for serializing the model into JSON.

This means you can use any of its annotations to customize the JSON output, e.g. @JsonIgnore to exclude the inverse relationship from Address to Customer:

@Entity

public class Address {

@Id

private long id;

@ManyToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "customer_id")

@JsonIgnore

private Customer customer;

private String street;

private String city;

...

}Note that Address itself isn’t marked with @MaterializeAggregate, i.e. it won’t be materialized into an aggregate view by itself.

After using JPA’s EntityManager to insert or update a few customers,

let’s take a look at the aggregates table which has been populated by the listener

(value schema omitted for the sake of brevity):

> select * from aggregates;

| rootType | keySchema | rootId | materialization | valueSchema |

| customers-complete

| {

"schema" : {

"type" : "struct",

"fields" : [ {

"type" : "int64",

"optional" : false,

"field" : "id"

} ],

"optional" : false,

"name" : "customers-complete.Key"

}

}

| { "id" : 1004 }

| { "schema" : { ... } }

| {

"id" : 1004,

"firstName" : "Anne",

"lastName" : "Kretchmar",

"email" : "annek@noanswer.org",

"tags" : [ "long-term", "vip" ],

"birthday" : 5098,

"category" : {

"id" : 100001,

"name" : "Retail"

},

"addresses" : [ {

"id" : 16,

"street" : "1289 University Hill Road",

"city" : "Canehill",

"state" : "Arkansas",

"zip" : "72717",

"type" : "SHIPPING"

} ]

} |The table contains these columns:

-

rootType: The name of the aggregate as given in the@MaterializeAggregateannotation -

rootId: The aggregate’s id as serialized JSON -

materialization: The aggregate itself as serialized JSON; in this case a customer and their addresses, category etc. -

keySchema: The Kafka Connect schema of the row’s key -

valueSchema: The Kafka Connect schema of the materialization

Let’s talk about the two schema columns for a bit. JSON itself is quite limited as far as its supported data types are concerned. So for instance we’d loose information about a numeric field’s value range (int vs. long etc.) without any additional information. Therefore the listener derives the corresponding schema information for key and aggregate view from the entity model and stores it within the aggregate records.

Now Jackson itself only supports JSON Schema, which would be a bit too limited for our purposes. Hence the example implementation provides custom serializers for Jackson’s schema system, which allow us to emit Kafka Connect’s schema representation (with more precise type information) instead of plain JSON Schema. This will come in handy in the following when we’d like to expand the string-based JSON representations of key and value into properly typed Kafka Connect records.

Capturing Changes to the Aggregate Table

We now have a mechanism in place which transparently persists aggregates into a separate table within the source database, whenever the application data is changed through Hibernate. Note that this happens within the boundaries of the source transaction, so if the same would be rolled back for some reason, also the aggregate view would not be updated.

The Hibernate listener uses insert-or-update semantics when writing an aggregate view, i.e. for a given aggregate root there’ll always be exactly one corresponding entry in the aggregate table which reflects its current state. If an aggregate root entity is deleted, the listener will also drop the entry from the aggregate table.

So let’s set up Debezium now to capture any changes to the aggregates table:

curl -i -X POST \

-H "Accept:application/json" \

-H "Content-Type:application/json" \

http://localhost:8083/connectors/ -d @- <<-EOF

{

"name": "inventory-connector",

"config": {

"connector.class": "io.debezium.connector.mysql.MySqlConnector",

"tasks.max": "1",

"database.hostname": "mysql",

"database.port": "3306",

"database.user": "debezium",

"database.password": "dbz",

"database.server.id": "184054",

"database.server.name": "dbserver1",

"database.whitelist": "inventory",

"table.whitelist": ".*aggregates",

"database.history.kafka.bootstrap.servers": "kafka:9092",

"database.history.kafka.topic": "schema-changes.inventory"

}

}

EOFThis registers the MySQL connector with the "inventory" database (we’re using an expanded version of the schema from the Debezium tutorial), capturing any changes to the "aggregates" table.

Expanding JSON

If we now were to browse the corresponding Kafka topic, we’d see data change events in the known Debezium format for all the changes to the aggregates table.

The "materialization" field with the records' "after" state still is a single field containing a JSON string, though.

What we’d rather like to have is a strongly typed Kafka Connect record, whose schema exactly describes the aggregate structure and the types of its fields.

For that purpose the example project provides an SMT (single message transform) which takes the JSON materialization and the corresponding valueSchema and converts this into a full-blown Kafka Connect record.

The same is done for keys.

DELETE events are rewritten into tombstone events.

Finally, the SMT re-routes every record to a topic named after the aggregate root,

allowing consumers to subscribe just to changes to specific aggregate types.

So let’s add that SMT when registering the Debezium CDC connector:

...

"transforms":"expandjson",

"transforms.expandjson.type":"io.debezium.aggregation.smt.ExpandJsonSmt",

...When now browsing the "customers-complete" topic, we’ll see the strongly typed Kafka Connect records we’d expect:

{

"schema": {

"type": "struct",

"fields": [

{

"type": "int64",

"optional": false,

"field": "id"

}

],

"optional": false,

"name": "customers-complete.Key"

},

"payload": {

"id": 1004

}

}

{

"schema": {

"type": "struct",

"fields": [ ... ],

"optional": true,

"name": "urn:jsonschema:com:example:domain:Customer"

},

"payload": {

"id": 1004,

"firstName": "Anne",

"lastName": "Kretchmar",

"email": "annek@noanswer.org",

"active": true,

"tags" : [ "long-term", "vip" ],

"birthday" : 5098,

"category": {

"id": 100001,

"name": "Retail"

},

"addresses": [

{

"id": 16,

"street": "1289 University Hill Road",

"city": "Canehill",

"state": "Arkansas",

"zip": "72717",

"type": "LIVING"

}

]

}

}To confirm that these are actual typed Kafka Connect records and not just a single JSON string field, you could for instance use the Avro message converter and examine the message schemas in the schema registry.

Sinking Aggregate Messages Into Elasticsearch

The last missing step is to register the Confluent Elasticsearch sink connector, hooking it up with the "customers-complete" topic and letting it push any changes to the corresponding index:

curl -i -X POST \

-H "Accept:application/json" \

-H "Content-Type:application/json" \

http://localhost:8083/connectors/ -d @- <<-EOF

{

"name": "es-customers",

"config": {

"connector.class": "io.confluent.connect.elasticsearch.ElasticsearchSinkConnector",

"tasks.max": "1",

"topics": "customers-complete",

"connection.url": "http://elastic:9200",

"key.ignore": "false",

"schema.ignore" : "false",

"behavior.on.null.values" : "delete",

"type.name": "customer-with-addresses",

"transforms" : "key",

"transforms.key.type": "org.apache.kafka.connect.transforms.ExtractField$Key",

"transforms.key.field": "id"

}

}

EOFThis uses Connect’s ExtractField transformation to obtain just the actual id value from the key struct and use it as key for the corresponding Elasticsearch documents.

Specifying the "behavior.on.null.values" option will let the connector delete the corresponding document from the index when encountering a tombstone message (i.e. a message with a key but without value).

Finally, we can use the Elasticsearch REST API to browse the index and of course use its powerful full-text query language to find customers by the address or any other property embedded into the aggregate structure:

> curl -X GET -H "Accept:application/json" \

http://localhost:9200/customers-complete/_search?pretty

{

"_shards": {

"failed": 0,

"successful": 5,

"total": 5

},

"hits": {

"hits": [

{

"_id": "1004",

"_index": "customers-complete",

"_score": 1.0,

"_source": {

"active": true,

"addresses": [

{

"city": "Canehill",

"id": 16,

"state": "Arkansas",

"street": "1289 University Hill Road",

"type": "LIVING",

"zip": "72717"

}

],

"tags" : [ "long-term", "vip" ],

"birthday" : 5098,

"category": {

"id": 100001,

"name": "Retail"

},

"email": "annek@noanswer.org",

"firstName": "Anne",

"id": 1004,

"lastName": "Kretchmar",

"scores": [],

"someBlob": null,

"tags": []

},

"_type": "customer-with-addresses"

}

],

"max_score": 1.0,

"total": 1

},

"timed_out": false,

"took": 11

}And there you have it: a customer’s complete data, including their addresses, categories, tags etc., materialized into a single document within Elasticsearch. If you’re using JPA to update the customer, you’ll see the data in the index being updated accordingly in near-realtime.

Pros and Cons

So what are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach for materializing aggregates from multiple source tables compared to the KStreams-based approach?

The big advantage is consistency and awareness of transactional boundaries, whereas the KStreams-based solution in its suggested form was prone to exposing intermediary aggregates. For instance, if you’re storing a customer and three addresses, it might happen that the streaming query first creates an aggregation of the customer and the two addresses inserted first, and shortly thereafter the complete aggregate with all three addresses. This not the case for the approach discussed here, as you’ll only ever stream complete aggregates to Kafka. Also this approach feels a bit more "light-weight", i.e. a simple marker annotation (together with some Jackson annotations for fine-tuning the emitted JSON structures) is enough in order to materialize aggregates from your domain model, whereas some more effort was needed to set up the required streams, temporary tables etc. with the KStreams solution.

The downside of driving aggregations through the application layer is that it’s not fully agnostic to the way you access the primary data. If you bypass the application, e.g. by patching data directly in the database, naturally these updates would be missed, requiring a refresh of affected aggregates. Although this again could be done through change data capture and Debezium: change events to source tables could be captured and consumed by the application itself, allowing it to re-materialize aggregates after external data changes. You also might argue that running JSON serializations within source transactions and storing aggregates within the source database represents some overhead. This often may be acceptable, though.

Another question to ask is what’s the advantage of using change data capture on an intermediary aggregate table over simply posting REST requests to Elasticsearch. The answer is the highly increased robustness and fault tolerance. If the Elasticsearch cluster can’t be accessed for some reason, the machinery of Kafka and Kafka Connect will ensure that any change events will be propagated eventually, once the sink is up again. Also other consumers than Elasticsearch can subscribe to the aggregate topic, the log can be replayed from the beginning etc.

Note that while we’ve been talking primarily about using Elasticsearch as a data sink, there are also other datastores and connectors that support complexly structured records. One example would be MongoDB and the sink connector maintained by Hans-Peter Grahsl, which one could use to sink customer aggregates into MongoDB, for instance enabling efficient retrieval of a customer and all their associated data with a single primary key look-up.

Outlook

The Hibernate ORM extension as well as the SMT discussed in this post can be found in our examples repository. They should be considered to be at "proof-of-concept" level currently.

That being said, we’re considering to make this a Debezium component proper, allowing you to employ this aggregation approach within your Hibernate-based applications just by pulling in this new component. For that we’d have to improve a few things first, though. Most importantly, an API is needed which will let you (re-)create aggregates on demand, e.g. for existing data or for data updated by bulk updates via the Criteria API / JPQL (which will be missed by listeners). Also aggregates should be re-created automatically, if any of the referenced entities change (with the current PoC, only a change to the customer instance itself will trigger its aggregate view to be rebuilt, but not a change to one of its addresses).

If you like this idea, then let us know about it, so we can gauge the general interest in this. Also, this would be a great item to work on, if you’re interested in contributing to the Debezium project. Looking forward to hearing from you, e.g. in the comment section below or on our mailing list.

Thanks a lot to Hans-Peter Grahsl for his feedback on an earlier version of this post!

About Debezium

Debezium is an open source distributed platform that turns your existing databases into event streams, so applications can see and respond almost instantly to each committed row-level change in the databases. Debezium is built on top of Kafka and provides Kafka Connect compatible connectors that monitor specific database management systems. Debezium records the history of data changes in Kafka logs, so your application can be stopped and restarted at any time and can easily consume all of the events it missed while it was not running, ensuring that all events are processed correctly and completely. Debezium is open source under the Apache License, Version 2.0.

Get involved

We hope you find Debezium interesting and useful, and want to give it a try. Follow us on Twitter @debezium, chat with us on Zulip, or join our mailing list to talk with the community. All of the code is open source on GitHub, so build the code locally and help us improve ours existing connectors and add even more connectors. If you find problems or have ideas how we can improve Debezium, please let us know or log an issue.